UPDATE, 11 December 2002. Following the launch of the First indicative NDC for the Sahrawi Republic in 2021 (see the article below from November 2021), we’ve been working to highlight issues around climate change and climate justice in relation to the Western Sahara conflict. As part of these activities, I’ve prepared a briefing on theses isues which you can download here (updated August 2023). The briefing is a draft, and will continue to evolve. A more detailed post on the activities around climate change and the Wetern Sahara conflict will follow in due course.

Last week I travelled to Glasgow with colleagues from Western Sahara and the UK to launch an indicative Nationally Determined Contribution (iNDC) – essentially a national climate change plan – for the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR). The launch took place at the COP26 Coalition People’s Summit for Climate Justice, and was supported by War on Want. This post provides some background to the iNDC and discusses the critical issues of climate justice that the iNDC addresses (including why it is an ‘indicative’ NDC). You can download the full text of the iNDC here (in English), along with the press release in English, French and Spanish. At the end of this article there are a number of videos from the iNDC launch, and from subsequent coverage.

The Sahrawi iNDC addresses climate change mitigation and adaptation in the non-self-governing territory of Western Sahara and the Sahrawi refugee camps in neighbouring Algeria. It also addresses issues of climate justice associated with the conflict between the Sahrawi national liberation movement and Morocco, recognised by the UN as the two equal parties to the conflict. The conflict has increased the exposure and vulnerability of the Sahrawi people to climate change impacts. At the same time, the SADR’s exclusion from global climate governance and finance mechansims means it cannot access the technical and financial support it needs to address these impacts. Meanwhile, Morocco uses these same governance and finance mechanisms to strengthen its occupation of Western Sahara. The iNDC affirms the SADR’s commitment to the goals and principles of the Paris Agreement, and provides a list of mitigation and adaptation actions.

What is a Nationally Determined Contribution?

Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) are documents that governments submit to the Secretariat of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), setting out the actions they intend to take to address climate change. These actions include mitigation actions, which reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and adaptation actions, which aim to reduce the impacts of climate change on people, infrastructure, the environment and so on. Actions may be unconditional, meaning that a government/country intends to take them anyway, or conditional, which means they are dependent on external technical and/or financial support. This is why there has been so much discussion about climate finance and who gets it – finance is critical for cash-strapped developing countries if they are to implement their mitigation and adaptation actions.

What is the political and historical context, and why is this NDC ‘indicative’?

Western Sahara is defined by the United Nations Special Committee on Decolonization as a non-self-governing territory or NSGT. These are “”territories whose people have not yet attained a full measure of self-government.” In other words territories in which the decolonisation process is not yet complete.

Western Sahara was a Spanish colony until 1975, when Spain pulled out and Morocco and Mauritania invaded and claimed the territory for themselves, despite an earlier ruling by the International Court of Justice that dismissed their claims to the territory. The Frente Polisario, the Western Saharan independence movement established some years earlier, fought Morocco and Mauritania on behalf of the Sahrawi people and their right to self-determination as recognised by the UN under resolutions 621 (1988), 690 (1991), 809 (1993) and 1033 (1995), and subsequently reiterated, most recently in 2021. Mauritania withdrew from the conflict and renounced its claim to the southern part of Western Sahara in 1979, but Morocco fought on. The Polisario declared a Sahrawi state, the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), in February 1976, which they intended to govern a unified, independent Western Sahara.

In 1991, the UN brokered a ceasefire between Morocco and the Polisario, and established the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara (MINURSO). By 1991, Morocco had seized around 80% of Western Sahara and constructed a 2700 km military wall, the ‘Berm‘ to secure the territory it occupied. Under the UN ceasefire, Western Sahara was divided into Moroccan occupied territory west and north of the Berm, Polisario held territory east and south of the Berm, and a ‘buffer strip’ extending 5km east of the Berm to separate the warring parties, and from which they were prohibited.

Today, over 500,000 people live in Moroccan occupied Western Sahara. Most of these are Moroccan settlers, encouraged to move to the occupied territory by their government through financial incentives. The population of native Sahrawis in the occupied territory is probably somewhere in the region of 100,000. An estmated 60,000 Sahrawi live in the Polisario controlled areas, where limited resources, minimal infrastructure and risks associated wirth renewed conflict constrain settlment. The majority of the Sahrawi population, estimated at 173,600 in a 2018 census, live in five large refugee camps around the Algerian city of Tindouf, close to the border with Western Sahara. The government of the SADR is based in the refugee camps. The SADR is a founding member of the African Union and has been formally recognised by some 80 countries. However, because of the conflict, the SADR is not yet a UN member state.

In November 2020, the ceasefire broke down when Morocco occupied part of the buffer zone, expanding its territorial occupation of Western Sahara.

It is in this context that we developed and launched the indicative NDC. Indicative, because countries can only submit a formal NDC if they are a party to the UNFCCC and a signatory to the Paris Agreement, which provides the framework for global climate governance of which NDCs are a part. To be a party to the UNFCCC or a signatory to the Paris Agreement, a country must be a UN member state. As the SADR is not yet a UN member state, it cannot be a party to the UNFCCC or a signatory to the Paris Agreement, so cannot submit a formal NDC. This ‘indicative’ NDC or ‘iNDC’ signals the SADR’s commitment to the Paris Agreement goals and principles, and its desire to participate in international process and mechanisms to address climate change. More on that below, when we address the climate justice aspects of the iNDC.

What are the climate change issues in Western Sahara?

Western Sahara and the displaced Sahrawi population (including the refugees and those who have settled in the Polisario controlled areas east of the Berm) are exposed to a number of climate change hazards and risks. Indeed, Western Sahara and the refugee camps are both highly exposed and highly vulnerable to climate change, as a result of geographic location and underlying socio-economic conditions respectively.

The refugee camps experience periodic, devastating floods that destroy homes, schools, health centres and other infrastructure, interupting food distribution, education and other activities. Floods cause fatalities and have significant impacts on physical and mental health. Floods are associated with intense rainfall events, and extreme rainfall intensity is increasing as a result of climate change, increasing flood risk.

The Polisario controlled areas of Western Sahara and the refugee camps are situated at the boundary between zones of high and extreme risk associated with heat exposure for global heating of 1.5°-3°C. Extreme risk is associated with potentially fatal wet-bulb temperatures above 34°C. These areas already regularly experience absolute temperatures above 50°C, and these episodes will become much more frequent. Extreme temperatures have impacts not just on heath but on infrastructure, for example increasing the risk of power outages.

Much of the Atlantic coast of Western Sahara is low-lying, and key settlements and infrastructure are at risk from sea-level rise. Changes in ocean temperature, salinity, chemisty and circulation, storm activity and wave height have the potential to adversely affect economically important fisheries.

The Sahrawi refugees are heavily dependent on humanitarian food aid. However, after 46 years of exile, they are experiencing the impacts of donor fatigue, and food aid in any case is lacking in key nutrients obtained from fresh food such as fruits and vegetables. Child malnutrition is widespread in the camps. To address these problems, the Sahrawi refugees are developing their own novel systems of food production. This is a challenge in the harsh desert environment, and climate change will make it more challenging through more extreme high temperatures and impacts on already scarce water resources.

The Sahrawi are nomadic pastoralists by tradition, and before the conflict lived mostly by herding camels and goats. This gave them an intimate knowledge of the landscape and its resources – knowledge that today could be used to track and manage the impacts of climate change. But their forced sedentarisation as a result of the conflict means this knowledge is being lost, undermining their adaptive capacity. The small number of Sahrawi that do practice pastoralism in the liberated territory controlled by the Polisario/SADR have to contend with mines, unexploded ordnance including cluster munitions, and now a renewal of the conflict which means shelling and aerial bombardment including drone attacks on vehicles – both military and civilian.

There are more direct impacts of the conflict too. For example, the Berm cuts across numerous drainage systems, preventing runoff reaching the downstream sections of channels (usually east of the Berm), and starving ecosystems of moisture (Figure 1).

Ultimately, tackling the above vulnerabilities, risks and impacts requires an end to the conflict, the reunification of Western Sahara, and the dismantling of the Berm. However, there are actions that can be taken to reduce risks, improve food production, maintain traditional knowledge, and build capacity, under the current circumstances. There are also actions that can be taken to support the development of a low-carbon society and economy in the camps and the liberated territory, building on the Sahrawi government’s historical implementation of decentralised renewables. A list of mitigation and adaptation actions, and actions that can be taken to build institutional capacity, is included in the iNDC.

Climate (in)justice and climate colonialism

The SADR’s status as a non-UN member state means that it cannot be a party to the UNFCCC or a signatory to the Paris Agreement. This means it cannot participate in global climate negotiations or have an official presence at events like COP26. In short, the SADR is excluded from the UN climate system and is thus denied a voice. (‘COP’ stands for Conference of the Parties, and these are parties to the UNFCCC. This is why we launched the NDC at an informal side event organised by the COP26 Coalition, which was established to give a voice to those who had no voice at COP26.)

Denying a nation and a people a voice in global climate negotiations (and the Sahrawie are not alone here) is bad enough. But this is only one aspect of the climate injustice imposed on the SADR and the Sahrawi people. Exclusion from the UN climate system means they cannot access the technical and financial support available to other developing countries. This means they are severely constrained in their capacity to address the climate change threats they face, and to pursue energy transitions. While not yet a UN member state, Western Sahara is recognised as a distinct territorial entity by the United Nations (as a NSGT), and the SADR, via the Frente Polisario independence movement from which the government is drawn, is recognised by the UN as the representative of the people of Western Sahara, whose right to self-determination is asserted in numerous UN resolutions.

But exclusion of the Sahrawi from global governance and finance mechanisms is just one side of a coin. The other is Morocco’s skifull use of these same mechanisms to position itself as a climate leader and strengthen its occupation of Western Sahara.

In 2019, Morocco received $293.8m in formal climate finance from multilateral climate funds, compared to $74.4 for Mauritania and $13.8 for Algeria. The SADR received nothing. Morocco likely received much more than this in terms of climate finance through bilateral development assistance, multilateral development banks and private finance.

This represents a huge assymmetry and a huge injustice. Morocco has increased the exposure and vulnerability of the Sahrawis by occupying their homeland, displacing most of the population, denying them access to their own natural and economic resources, forcing them to live in areas that have the fewest resources and that are most exposed to the impacts of climate change, preventing them from accessing external technical and financial assistance as a result of the unresolved conflict, and marginalising those Sahrawi living under occupation. Yet Morocco receives large amounts of climate finance, while the SADR receives nothing. In this way, the system of global climate governance and finance favours one actor in a conflict while disadvantaging the other. (At this point it is worth highlighting that the UN recognises Morocco and the Frente Polisario – from which the government of the SADR is drawn – as the two, equal parties to the conflict, and the Polisario as the sole representative of the Sahrawi people.) This is the very definition of climate injustice – systems, actions and finance intended to address climate change that instead systematically reinforce the structures and power relations that drive vulnerability.

But there is more to the climate justice aspect of this conflict.

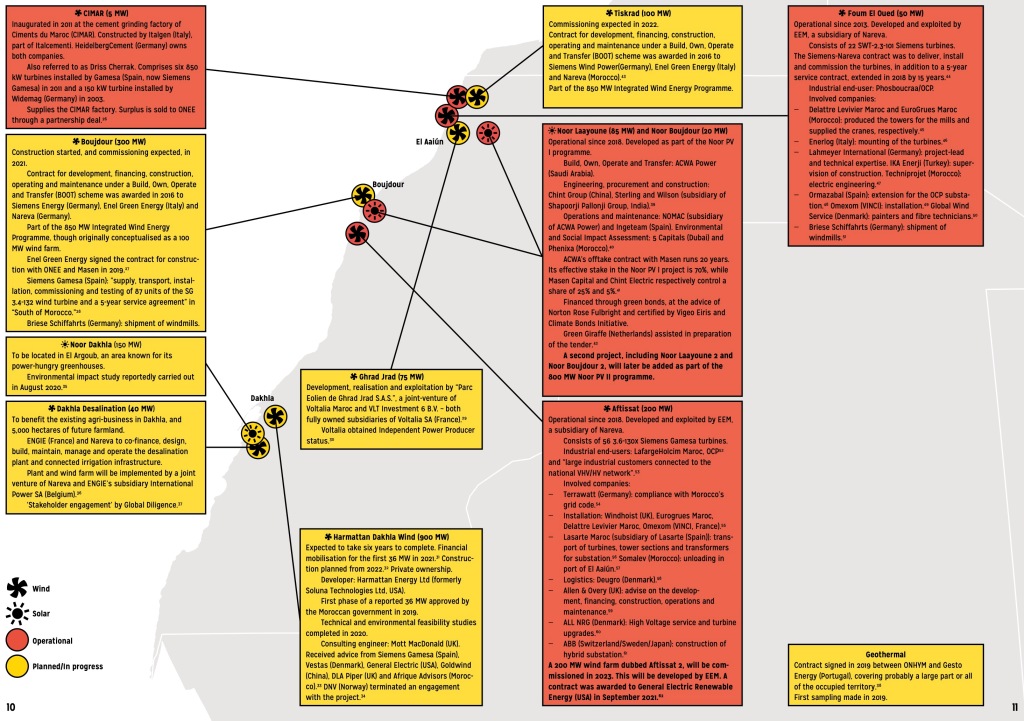

Morocco is vigorously pursuing renewable energy projects in occupied Western Sahara (Figure 2). In 2006 it applied to the UN Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) for funding for the Foum el-Oued wind farm in the occupied territory. Its application was rejected, but Morocco secured private finance for the construction of the wind farm, which is now registered with a private, voluntary carbon offsetting scheme. Rewewable energy in occupied Western Sahara enables settlement in the occupied territory by Moroccan nationals and primarily benefits elite Moroccan and foreign financial and business interests with links to the royal palace.

In addition, Morocco relies heavily on renewables in occupied Western Sahara to meet its own climate mitigation targets. A recent study by Western Sahara Resource Watch estimated that nearly half of Morocco’s wind energy production and up to a third of its solar energy production is expected to be generated in occupied Western Sahara by 2030. This means that Morocco is dependent on an illegal military occupation for meeting the mitigation targets in its own NDC – an explicit, extreme and quite literal example of climate colonialism. The fact that statistics relating to current and future emissions mitigated by rewewables in occupied Western Sahara are accepted as part of Morocco’s formal NDC means that the UNFCCC is complicit in this climate colonialism. This is contrary to a number of principles set out in the Paris Agreement, including those of transparency and accurancy, which relate specificaly to NDCs.

More generally, the exclusion of the Sahrawis from global climate governance and finance mechanisms, and the erosion of traditional knowledge that is critical in tracking and responding to the impacts of climate change, is contrary to the adaptation principles in paragraph 5 of Article 7 of the Paris Agreement.

Finally, of course, the Sahrawis have made a negligible contribution to global carbon emissions, but are set to suffer disproportionately from climate change. This is particularly true for those living in refugee camps in the inhospitable Algerian desert, where conditions are harsher, resources scarcer, and climate change impacts more challenging than in Western Sahara itself.

Mapping tacit support for climate colonialism

Morocco’s climate colonialism is given tacit support by many organisations, including research organisations, media outlets, and donors of development aid. Western Sahara is defined as a distinct territorial entity by the United Nations, and is recognised as such by most countries (including the UK). However, many organisations that work on climate change and fund climate change initiatives represent it as wholly or partly integrated into Morocco, effectively endorsing Morocco’s occupation of the territory. This has important implications for recognition of and support for climate action by the SADR.

The US Foreign Assistance website shows Western Sahara as part of a ‘greater Morocco’, which is perhaps unsurprising given Trump’s unliateral recognition of Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara as a quid pro quo for normalisation of relations with Israel. Nonetheless, the USAID website employs a more ‘diplomatic’ map that sidesteps the issue by omitting national borders.

Perhaps most surprising is the German government development agency GIZ‘s representation of Western Sahara as part of Morocco. This is in stark contrast to Agence Française de Développement (AFD), which shows Western Sahara as a distinct, named territory, albeit stippled to indicate its ‘contested’ status. This is striking given France’s longstanding support for Morocco at the expense of the Sahrawi people. Echoing France’s position, the African Development Bank shows Western Sahara as a distinct territory, but represents the border with Morocco as a dashed line. However, the World Bank represents Western Sahara as a distinct territory and does not differentiate its status from that of other countries in its maps. It should be emphasised that Western Sahara’s status as a non-self-governing teritory whose status is to be determined by a referendum on self-determination is clear in multiple UN resolutions. In this sense, there is no question as to whether it is or is not part of Morocco, and Western Sahara is subject to a military occupation, not a territorial dispute.

It is increasingly common for organisations to represent Moroccan occupied Western Sahara and the areas controlled by the Polisario/SADR as separate territorial entities, with the Berm represented as an international border. This is factually incorrect and indicates an ignorance of Western Sahara’s formal status. For example, Carbon Brief shows the Moroccan occupied territory as part of Morocco, and the Polisario controlled areas as separate territory entity or country. This error is repeated in articles on climate justice and diversity in climate science research, somewhat undermining Carbon Brief’s otherwise excellent and authoritiative reputation. The same mistake is made by the UK government’s Development Tracker website, despite the UK’s formal support for the UN position and for the self-determination process.

The Guardian newspaper repeats the same error in a November 2021 article on changes in climate ambition as represented by NDCs submitted in the run-up to COP26. As it explicitly addresses the content of NDCs, the map reproduced in this article is an explicit endorsement of Morocco’s dependence on mitigation activities in occupied Western Sahara, and thus of Morocco’s climate colonialism. (We wrote to the Guardian about this but the letter, which adhered rigorously to their guidelines, was not published and we received no response, despite the paper’s longstanding coverage of climate justice.)

The Guardian article states that its analysis is based on data from Climate Action Tracker (CAT). However, the CAT map represents Western Sahara as a distinct territorial entity, and the colour coding indicating Morocco’s mitigation status is confned within Morocco’s recognised territorial borders. Prior to September 2021, CAT had shown Western Sahara as part of Morocco. It is notable that the correction to their map coincided with the downgrading of Morocco’s mitigation performance from ‘1.5°C compatible’ to ‘almost sufficient’, although it is not clear if these changes were related. CAT’s assessment of Morocco’s performance presumably is based on the Moroccan NDC, and it seems likely that Morocco’s performance would be downgraded further if its extensive renewables developments in occupied Western Sahara were omitted.

What needs to be done?

For the international system that has emerged around global climate governance and finance to have credibiity and legitimacy, the Sahrawis and other marginalised peoples need to be included in climate governance and finance mechanisms. Given Western Sahara’s clear status as a non-self-governing territory, the existence of a formal (albeit stalled) decolonisation process based on the principle of self-determination, SADR’s membership of the African Union, its widespread diplomatic recognition, and the publishing of its first indicative NDC, the case for inclusion of the SADR is clear. For the case of the SADR and the non-self-governing territory of Western Sahara, the following measures are required:

- Acceptance of Morocco’s NDC by the UNFCCC should be conditional on the exclusion of emissions and mitigation actions in occupied Western Sahara, to comply with the conditions of transparency, accuracy, comparibilty, consistency, avoiding double counting, and the wider principle of equity (this has a precedent in the recent ruling of the EU General Court that Western Sahara is separate and distinct from Morocco and should be treated as such in relation to international agreements);

- Organisations working on climate change must recognise that Western Sahara is a distinct territorial entity and the Berm is not an international border, and should reflect this in their published materials;

- The SADR should be granted observer status at the UNFCCC immediately, with a view to full participation in climate negotiations;

- The SADR’s iNDC should be accepted as a formal NDC;

- The SADR should have access to climate finance to build its capacity to respond to climate change (including updating its NDC and developing its capacity for emissions calculations and MRV) and address the urgent and severe impacts of climate change, particularly in the Sahrawi refugee camps.

Given the current focus on climate justice and the clamour for the voices of those hitherto excluded from climate negotiations to be heard, Western Sahara represents a litmus test for climate justice. As things stand, very few self-styled champions of climate justice are passing this test.

_________________________________

See below for some videos related to the iNDC launch.

First up, Mohamed Sulimain on the impacts of climate change and climate justice.

Next, Senia Bachir talking about the conflict, life as a refugee, climate change and climate injustice.

Here is Mohamed Ould Cherif, President of the Sahrawi NGO Association pour la Sauvegarde de l’Environnement du Sahara Occidental (ASESO), talking about the environmental impacts and aspects nof the conflict.

Here is Taleb Brahim, talking about food production in the Sahrawi refugee camps. See more stories about Taleb’s work from the World Food Programme, Oxfam, and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Action Zone.

Nick Brooks and Ambassador Oubi Bouchraya Bachir, the Polisario representative to the EU and Europe, introducing the iNDC in Glasgow.

Interview by Democracy Now! covering the launch of the iNDC and the issues it addresses (video and transcript)